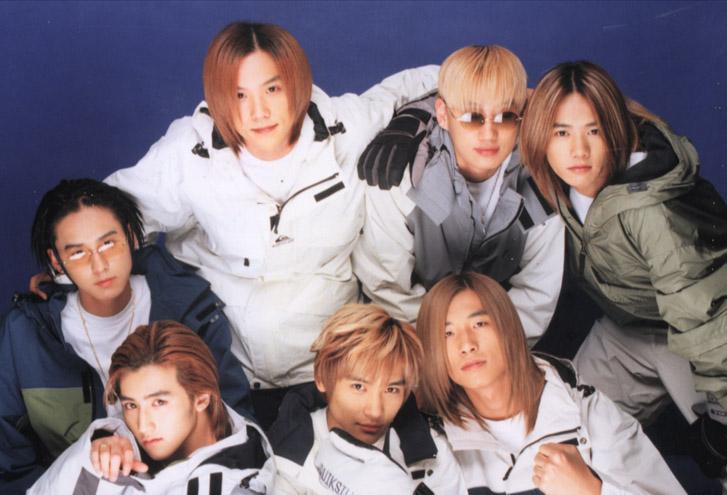

If you enjoyed my interview with Albert Kao, you may have caught yourself wondering, “Hmmm…I wonder what the optimal level of modularity is in the network of K-pop artists?” Fortunately, The Pudding released a semi-viral article discussing that exact question.

Now, unlike the agents in Albert’s modeling experiments, K-pop artists are not necessarily trying to optimize for correct information in a complex environment. They are, however, trying to optimize for something like “teens posting on Tik Tok,” “fans engaging in rabid Twitter behavior,” or “more people than seems reasonable watching YouTube videos.”

So, why is a larger group size potentially more effective in the K-pop ecosystem than the standard 3-5 members of most typical rock or vocal groups?

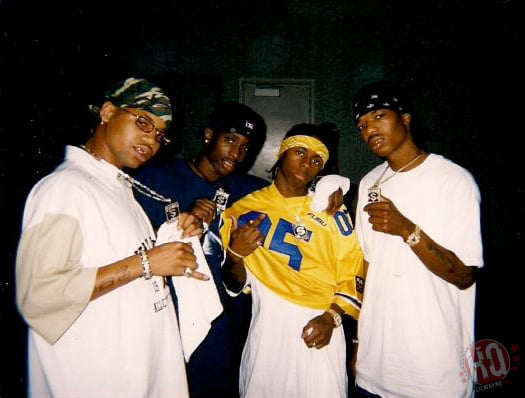

I think a better point of comparison for the K-pop group is the “hip-hop collective” rather than the “rock band.” While many hip-hop groups often have member counts more in line with rock groups, we often see the larger “collectives” in hip-hop approaching or superseding a similar size to the K-pop groups mentioned.

Most saliently, the Wu-Tang Clan had 9 members during its classic period (The RZA, The GZA, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Raekwon the Chef, Ghostface Killah, Inspectah Deck, U-God, and The Method [Man…Man…Man…] — Masta Killah was unfortunately left out of this classic intro.)

If you consider other groups from Cash Money Records, No Limit Records, Boot Camp Clik, or the Dungeon Family, it’s much more common to see loose collectives of 8-20 artists reorganized in endless permutations.

Notably, I remember being very confused by this as a 12-year-old watching music videos on The Box. I was like, “Why are the Cash Money Millionaires the same as The Hot Boys—what the hell is going on here?”

Parsing the relationship between the Big Tymers, The Hot Boys, and the Cash Money Millionaires—as well as BG, Lil Wayne, and Juvenile’s solo releases—was far too much to infer from a handful of music videos.

Anyway, in genres like hip-hop or K-pop where it’s very easy for artists to move in and out of different groups and constantly feature each other on songs, there seem to be “return on scale” effects.

The success of one member provides benefits to the whole group—and a single outsized success can be game-changing for the entire collective. A larger group size allows more opportunities for a single member or a single song to be successful by having more “shots on goal,” both in terms of number of people creating music as well as the different permutations of artists that can be created.

Similar “scenes” do form in rock, punk, and hardcore as well—it’s just that groups are more discrete. It’s not as easy to have members hop in and out of songs, be “featured” on tracks, or form subgroups from a larger collective.

My own history of being in bands, for example, is populated with a core group of probably 20-30 musicians from Chicago and the surrounding suburbs with a variety of other peripheral players.

I don’t have much experience in jazz scenes, but we see similar dynamics in the classic quartets, quintets, and trios that make up much of the jazz canon. Players moved in and out of different groups and formed larger “clusters” of a scene—even if they typically organized into groups of 3-5 for specific releases.

So, if we use a “hip hop collective” or a “jazz scene” or “5 hardcore bands from the same city that share the same members,” it’s actually not that surprising that K-pop groups have so many members.

[Notably, CL—one of K-pop’s biggest stars—has a song called “Lifted” that borrows its hook from “Method Man” mentioned above. The video also features Clifford himself making an appearance.]

It’s only surprising that all of the members in K-pop groups perform at once — although K-pop’s postmodern mishmash of genres that is hyper-optimized for YouTube’s engagement algorithm does facilitate a lot more stuff happening in one song, so there is actually room for three lead vocalists, three rappers, and 15 costume changes (and associated dance routines) all in one track.